Blog Post #6: A Behavioral Economics Perspective on Procrastination

Have you ever had an assignment due on Monday, but on Sunday night, you still haven't started? This is something that almost all students have experienced, and is definitely an experience I've had many times before, too. According to Joseph Ferrari, a professor of psychology at DePaul University, procrastination affects 20% of adults and 50% of university students. Procrastination refers to the act of “unnecessarily postponing decisions or actions,” even though we know we will suffer the consequences after. But why do we still procrastinate?

Surprisingly, some of the reasons why we procrastinate are not that obvious and could shock you. Many psychologists have found that anxiety, low self-esteem, and a lack of-self confidence are some key drivers of procrastination. A University of Melbourne Student Union article titled “The Psychology Behind Procrastination” breaks down two main behavior types that lead to procrastination.

The first behavior type encompasses people who avoid tasks completely because of anxiety. The worrier, the perfectionist, and the over-doer are three types of people who fall into this category. Common threads between them include the fear of failing, the fear of not being perfect, and the failure to prioritize tasks. These feelings make it hard for these types of people to get started on things early, leading them to leave tasks to the last minute instead.

The second behavior type that drives procrastination is boredom and frustration, which includes procrastinators like the crisis maker, the dreamer, and the defier. The crisis maker, in particular, is interesting because they believe that they perform best under pressure. Therefore, they justify leaving their tasks to the last minute because they believe that they get their best work done when they’re stressed. This makes sense because procrastination is often described as a “complex maladaptive reaction to various perceived stressors.” According to the article, procrastination is ultimately a "short-term solution to the immediate problem.”

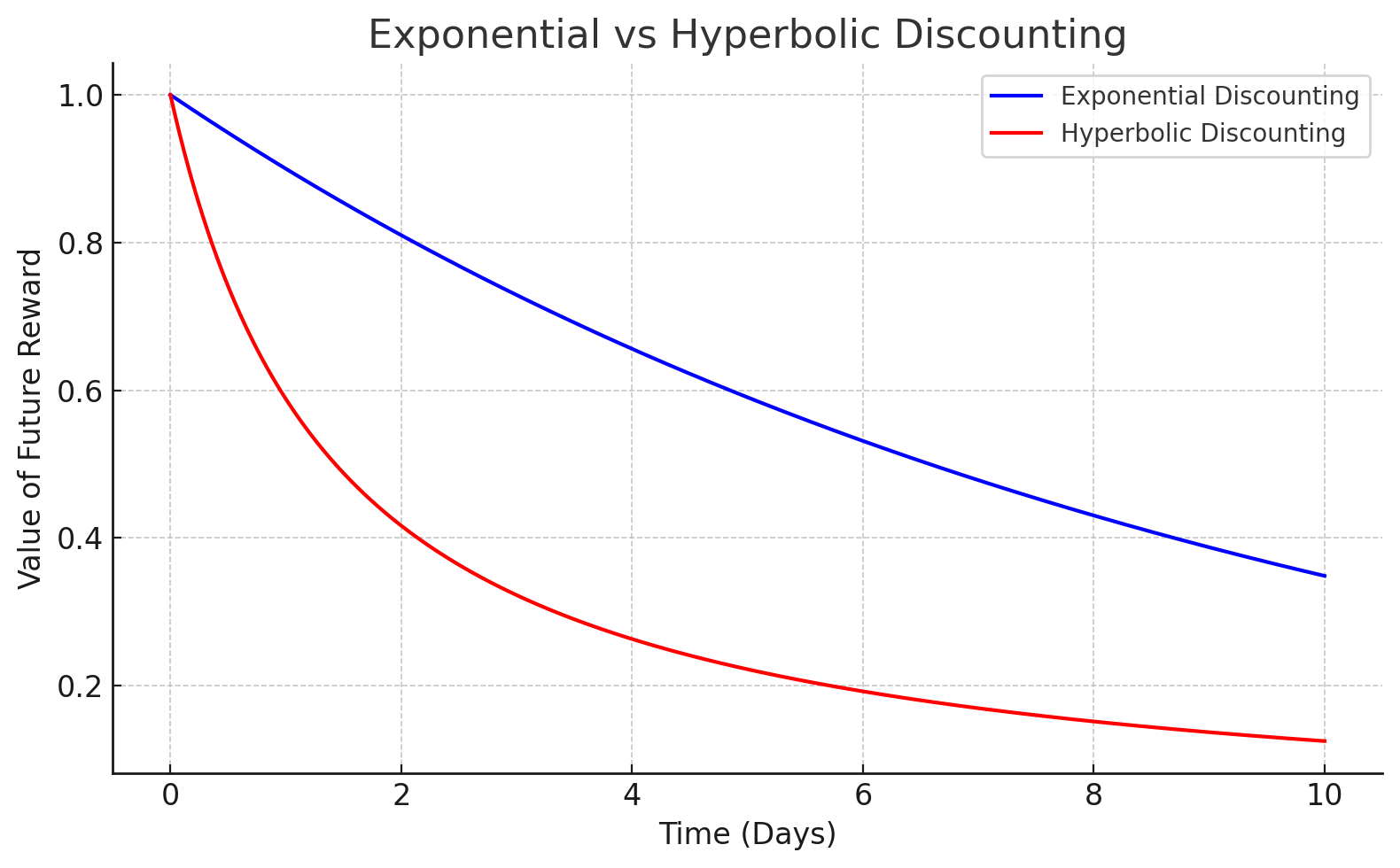

The idea that putting off your assignment will make you feel better temporarily but will make you feel much worse later on correlates to a key concept in behavioral economics and human decision-making called the “present bias”, or “hyperbolic discounting”. This concept refers to how people overvalue immediate comfort and undervalue future hardship. A Harvard Magazine article titled “The Marketplace of Perceptions” provides an overview of behavioral economists’ view on procrastination. Economics professor David Laibson states, “There’s a fundamental tension, in humans and other animals, between seizing available rewards in the present, and being patient for rewards in the future…People very robustly want instant gratification right now, and want to be patient in the future.” He used a famous example: “Now we want chocolate, cigarettes, and a trashy movie. In the future, we want to eat fruit, to quit smoking, and to watch Bergman films.” The same principle applies to something as common as procrastination; on a Sunday morning, we’d rather say yes to going out with our friends than to sitting down and starting a big project that is due on Monday. But on Sunday night, we’ll wish we had started the assignment earlier.

Economics can represent this behavior by comparing exponential and hyperbolic discounting side by side on a graph:

Source: The Economics of Procrastination

The red line (hyperbolic discounting) shows a steep decline. As soon as a reward is determined to not be immediate, its perceived value decreases dramatically. The catch? This is exactly how students, teachers, adults—really, everyone—thinks of procrastination.